Console History

2D Generations - 8-bit to 16-bit:

||

||  ||

||

Add-ons, CD-ROMS, FMV and early 3D gaming:

||

||  ||

||  ||

||  ||

||

3D Generations - 32-bit to 128-bit:

||

||  ||

||

||

||  ||

||

- 1. bias 3 a : bent, tendency b : an inclination of temperament or outlook; especially : a personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment.

Sega Master System vs Nintendo Entertainment System

| Lifespan: | 1986-1992 | |

|---|---|---|

| CPU: | 3.58 MHz Z80 | |

| Audio: | 4 Channels 3 | |

| Co-Processor: | VDP | |

| Resolutions: | 256x192, 256x224, 256x240 (PAL) 4 | |

| RAM: | 8KB | |

| Video RAM: | 16KB | |

| Color RAM: | 32 bytes5 | |

| Colors On Screen: | 32 (two 16-color palettes)6 |

|

| Color Palette: | 64 | |

| Sprite Max & Size: | 64 at 8x8, 8x16, 16x16, 16x327 |

|

| Sprites per Scanline: | 8 8 | |

| Storage: | Sega Card (32KB) Cartridge 1Mb - 4 Mbit |

9 10

9 10

| Lifespan: | 1986-199211 |

|---|---|

| CPU: | 1.79 MHz 6502 |

| Audio: | 5 Channels 12 13 |

| Co-Processors: | PPU, pAPU14, MMC15 |

| Resolution: | 256x224 visible of 256x24016 |

| RAM: | 2KB |

| Video RAM: | 2KB |

| Colors On Screen: | 16 (four 4-color background palettes + four 4-color sprite palettes)17 |

| Color Palette: | 52 |

| Sprite Max & Size: | 64 at 8x8 and 8x16 |

| Sprites per Scanline: | 8 18 |

| Storage: | Cartridge 1 Mbit - 4 Mbit Average: 1 Mbit |

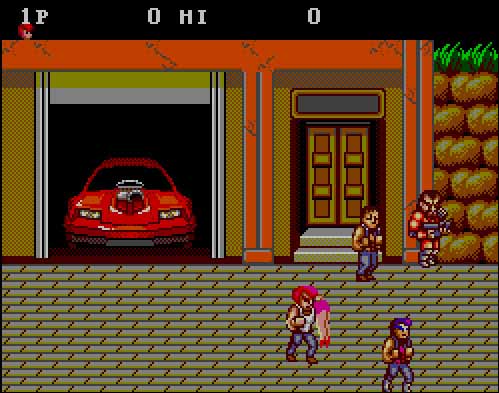

Hardware specifications for the 8-bit consoles (1982-1987) are relatively easy to read. The Sega Master System arguably trumped the Nintendo Entertainment System in most technical respects, aside from the base systems' audio capabilities. Both systems were also released nation wide in the United States in 1986.19 Yet technical superiority affects the market success of a console very little. Size and quality of a game console's library might be given lip service in comments and editorials, but games tend to play second fiddle to popularity and brand over the history of the game industry.

Third party developer (third party) support for the Sega Master System (SMS) was comparatively small due to the monopoly Nintendo designed for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Licensing contracts for the NES prevented third parties from making the same game on other consoles for two years.20 This fact was exacerbated by Nintendo's publishing empire in Japan, where most of the world's game developers and publishers survived the "crash" of 1984. Nintendo's affinity for legal recourse locked most third parties into sitting on their Intellectual Property (IP) or rebranding and selling it to other console manufacturers.

Nintendo's stringent publishing controls left them with less than ten third parties in 1986.21 While Nintendo was courting third party developers and establishing its dominance at retail in 198722, Sega was adapting its significantly larger arcade catalog to the SMS.23 As a result, the NES library only clearly surpassed its main rival console in quantity of quality titles after the 16-bit generation was in its stride in 1990.24

Nintendo's stringent publishing controls left them with less than ten third parties in 1986.21 While Nintendo was courting third party developers and establishing its dominance at retail in 198722, Sega was adapting its significantly larger arcade catalog to the SMS.23 As a result, the NES library only clearly surpassed its main rival console in quantity of quality titles after the 16-bit generation was in its stride in 1990.24

Sega's Master System is home to a number of exclusive titles, including the first console role playing games in the West. Phantasy Star and Miracle Warriors included innovative features such as animated 3D dungeons, five save anywhere save slots, female protagonists, diverse monster designs, and complex clue based puzzles. For every space ship shooter, "Mario" platformer or "Zelda" adventure game on the NES, the Master System had an exclusive with at least equal gameplay quality and better graphics. Yet the total US release list only added up to one hundred and fourteen titles, most of which were published, if not originally designed or recoded, by Sega themselves.

A controversial difference exists between companies like Sega and companies like Capcom, Nintendo, and Namco during these formative years of the game industry. Sega's focus on games throughout their time as a hardware manufacturer was focused on creating unique experiences and advancing the technology. Nearly all of Nintendo's mainline publishers, and Nintendo themselves, focused on creating popular game franchises. Exceptions to this rule exist on both sides, but the principle is dominant in the published software. What this means to the history of gaming is that a monumental battle occurred in game development theory immediately upon the arrival of Japan in the US game industry. Conceptually, the question these companies' games present is whether the consumer wanted unique experiences in high quantity and quality, or whether they wanted familiar experiences to be replicated. Game developers in this era, perhaps unconsciously, asked whether consumers wanted to try something new more frequently than they wanted to play the third, fourth or fifth iteration of essentially the same game.

In addition to exclusive unique games, a very notable peripheral was only released for the SMS, Liquid Crystal Display 3D glasses. These glasses plugged in to the secondary game card slot on the SMS, and synchronized opaque flashes on either eye with flashing character sprites on the television. The resulting effect produced a 3D effect far superior to red and blue card board glasses and is a technical marvel that is supposed to revolutionize television and movies in the new millennium.

A relatively short library includes Blade Eagle 3D, Maze Hunter 3D, Missile Defense 3D, Space Harrier 3D, Poseidon Wars 3D, Zaxxon 3D, and the Euro only release of Outrun 3D sum up the relatively small library of 3D games for the Master System. So unique were these glasses that Sega even included them as a pack in for the more expensive Master System console package. Notable as this peripheral was, what few consumers actually bought an SMS gravitated toward cheaper packages.

Despite these very notable facts, the Sega Master System was a total marketing failure for Sega in Japan and the United States. To its credit, the SMS actually dominated well into the mid 90's in Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Brazil, and revenue generated from these countries has caused a great deal of games to be produced. Many more Master System games were made for these markets that are actually compatible without modification with US Master Systems. Were there a sizeable retro-gaming market in the early 2000s, this too would be a notable fact about the Master System.

There are popular theories as to why the SMS was not a success in the United States. One very plausible reason is Nintendo's monopolistic licensing contracts with third parties. This left the SMS without popular third party titles available on a large enough scale to compete with the NES library. Another contributing factor was Sega's lack of a United States office at the time of the Master System's release. Sega sold the publishing and marketing rights to Tonka toys because Tonka had more resources to make the system a success. Unfortunately, the presentation by numerous sources is that Tonka sat on the Master System until their multi-year contract with Sega was up. This presentation is no doubt inaccurate to the reality of Nintendo's strangle hold on retailers from 1987 onward.

Facts state the case much more concisely. With relatively insignificant marketing, and the fact that Nintendo ensured that the console itself was not available on as many shelves as the NES, the Master System was actually doomed from the moment it landed on US shores. Well documented defects in the NES's quality control and design, which has caused up to 30% of systems shipped to stop playing games and all games to have noticeable glitching during scrolling scenes, were utterly overlooked by consumers.

The NES and SMS were Nintendo's and Sega's first entries in the video game console market in the United States. Nintendo and a group of less than ten third party developers helped to propel the NES to monumental success by 1988. Sega and a handful of other third parties supported the Master System with exclusive arcade and home-only game software, adding up to one hundred and fourteen titles. The Nintendo Entertainment System sold something around fifty million worldwide and saw seven hundred and sixty-one releases in the United States. Thirteen Million SMSs were sold worldwide from 1985-1998, and US support for the console was cut off around 1992.

In regard to what people were actually playing on each system, according to reviews online, over one hundred of the final US SMS library have been noted as having unique or highly polished gameplay, in such a way that they have received a recommendation from reviewers today. By comparison, roughly three hundred of the NES's final library of over seven hundred and sixty titles have been recommended for similar reasons. From 1986-1988, the SMS and NES had roughly the same number of titles which people have found worth mentioning. The majority of the NES's vastly larger library, and its lead in notable game titles, was gained after 1989, when the 16-bit era had already begun and the NES was the only mass market 8-bit platform.

- 1. Legacy Sega Consoles: Sega Master System, Sega of America (archive.org January 19, 2002).

- 2. Samuel N. Hart, A Brief History of Home Video Games: Side-by-side Comparison of the Sega Master System and Nintendo Entertainment System, Geek Comix (archive.org June 25, 2008).

- 3. 3 channel tone generator, white noise channel, mono Super Majik Spiral Crew's Guide to the Sega Master System (0.02) (smsc.txt) Basic Sound (Public Domain, SMSC, June 21, 1997, accessed March 11, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=Master%20System; internet.

- 4. Charles MacDonald, E-mail || Homepage, Sega Master System VDP documentation (msvdp.txt), 11.) Display timing (2002, accessed March 11, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=Master%20System; internet.

- 5. MacDonald, msvdp.txt, 5.) Color RAM.

- 6. Background patterns can use either palette, while sprite patterns can only use the second one. MacDonald, msvdp.txt, 5.) Color RAM.

- 7. 16x16 and 16x32 Sprites are only available when all sprites on screen are stretched, smsc.txt,

Register 81h.

- 8. msvdp.txt 10.) Sprites.

- 9. Hart, Side-by-side Comparison of the Sega Master System and Nintendo Entertainment System.

- 10. Nintendo of America, Systems: NES Specifications (archive.org June 15, 2001).

- 11. NES was test marketed in 500 to 600 retail stores in New York during Christmas, 1985, David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (New York: Random House, 1993), 169.

- 12. 2 Square Waves, 1 Triangle, 1 White Noise, 1 Delta Modulation Channel for samples, Uses the CPU. Brad Taylor, The NES sound channel guide 1.8 (nessound.txt), Introduction (July 27, 2000, accessed March 11, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=NES; internet.

- 13. Brad Taylor, NTSC delta modulation channel documentation 2nd release (DMC.txt), (February 19, 2003, accessed July 17, 2011) available from http://nesdev.parodius.com/dmc.txt; internet.

- 14. "virtual" sound unit inside CPU

- 15. Yoshi, Nintendo Entertainment System Documentation 2.0 (nestech.txt), 2. Acronyms (accessed March 11, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=NES; internet.

- 16. Martin Korth, Everynes - Nocash NES Specs (everynes.txt) PPU Dimensions & Timings (2004, accessed March 11, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=NES; internet.

- 17. everynes.txt PPU Palettes.

- 18. everynes.txt PPU Sprites.

- 19. Steven L. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001), 303.

- 20. Sheff, Game Over, 215.

- 21. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, 307.

- 22. Sheff, Game Over, 171.

- 23. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, 304.

- 24. Notable Games: 1985-1990, http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

TurboGrafx-16

| Lifespan: | 1989-1993 |

|---|---|

| CPU: | 7.16 MHz 8-bit HuC6280 4 |

| Audio: | 6 Channels (Uses CPU) 5 |

| Co-Processors: | 3.58 Mhz PSG 6 Video Processor: 16-bit HuC6270 7 Color Processor: HuC6260 8 |

| Resolutions: | 256x256 || 320x256 9 |

| RAM: | 8 KB |

| Video RAM: | 64 KB |

| Colors On Screen: | 480 (60-90 Average, ~128 Max in games) 10 |

| Color Palette: | 512 ( 32 Palettes of 16 colors each) 11 |

| Sprite Max & Size: | 64 at 16x16, 16x32, 16x64, 32x16, 32x32, and 32x64 pixels 12 |

| Sprites per Scanline: | 16 13 |

| Background Planes: | 1 Layer (Dynamic Tiles and Sprites were used to create up to four scrolling layers) |

| Storage: | HuCard 16Mbit (2.5MB), Average 4 Mbit CD-ROM |

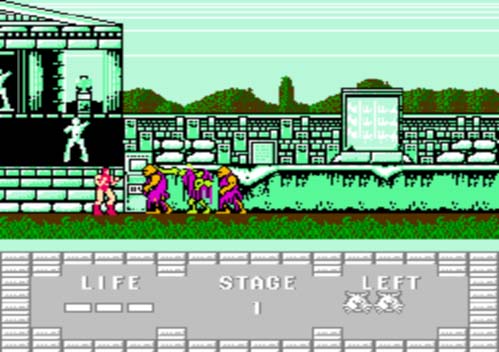

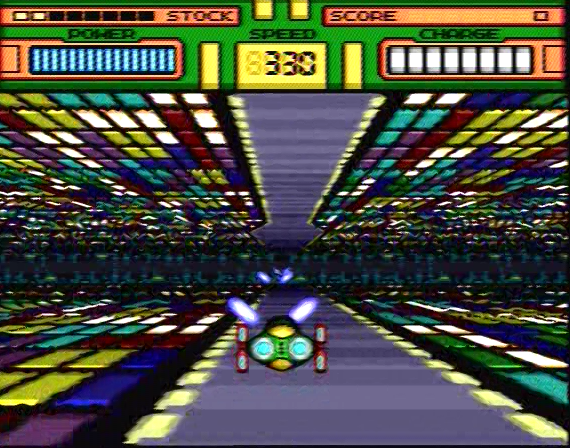

Just as the battle between the 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System was looking one-sided the first of many electronics giants entered the fray. The NEC manufactured TurboGrafx-16 (TG16) was released in 1989 in the US and displayed impressive visual quality, audio and effects compared to its 8-bit predecessors and its 16-bit competition. NEC's game console boasts relatively high amounts of colors on screen at once, software scaling in games like Afterburner (Japan),14 and multi-level backgrounds (parallax) in space ship shooters. Despite the TurboGrafx's 8-bit central processor these effects demonstrate a significant edge in horsepower over the later released, fully 16-bit, Super Nintendo. The relative color limitation for Sega's Genesis should also lend NEC proper respect for designing a state of the art game console. As a result, game magazines in 1989 painted a picture of the TG16 quickly becoming a major contender in the US game console wars.15 16

The PC-Engine was released one year before the Megadrive (Sega Genesis) in Japan. By 1989 the PC-Engine, renamed TurboGrafx-16, had over one hundred software titles published and ready to be localized for the US market.17 Nintendo's monopoly, and subsequent restrictive licensing contract with third party developers, contributed greatly to hindering the localization of most of these software titles.18 As Nintendo's licensing contract for the NES is understood, no game made for the NES could be made for another console within two years. So, popular NES software such as the original Megaman, released December of 1987, could not be released on the TurboGrafx until 1990. Nintendo Entertainment System owners would meanwhile be playing the third iteration of Megaman. Game developers already had to decide whether to spend their time and money producing a game for an unproven console. For the initial years following their release, developers for the TG16 and Sega Genesis could only release arcade adaptations, new games or completely reprogrammed and rebranded versions of NES software.

Nintendo owned at least ninety percent of the game console and software sales in Japan and the United States in 1989, so NES software took priority for third party developers.19 This left the TurboGrafx with a relatively small selection of titles from NEC and Hudson Soft. Probably to compensate for bad press, NEC took a marketing stance of only releasing the "best of the best" PC-Engine titles locally. Nevertheless, the final TG16 library pales in comparison to what was available for the PC-Engine in Japan.20 It is no coincidence that many of the games that were never localized were superior versions of popular NES software. The opinion, however, of journalist created history claims that what few PC-Engine titles were localized by NEC, Hudson, and a handful of third parties were not "fun," or popular enough, to make the console successful in the United States.21 22

Sega and Nintendo managed to publish and license enough games during the previous generation's formative years to be roughly equal in library by the end of 1989. During these years, Nintendo spent more time courting developers than making games. As a result, from 1990 to 1992, no console could compete with the flood of software releases on the NES.23 So non-Nintendo hardware should be viewed as a separate market during this time. In 1989 and 1990 the TG16 saw roughly the same amount of quality software releases as the Sega Genesis and Master System combined.24

Sega and Nintendo managed to publish and license enough games during the previous generation's formative years to be roughly equal in library by the end of 1989. During these years, Nintendo spent more time courting developers than making games. As a result, from 1990 to 1992, no console could compete with the flood of software releases on the NES.23 So non-Nintendo hardware should be viewed as a separate market during this time. In 1989 and 1990 the TG16 saw roughly the same amount of quality software releases as the Sega Genesis and Master System combined.24

NEC also took the cutting edge title in 1990 by releasing the CD-ROM add-on for the TurboGrafx. The Turbo CD added an additional library of over one hundred CD-ROM titles, including excellent Role Playing Games (RPGs). NEC promised an affordable price for their CD-ROM add-on, but the list price for the Turbo CD ended up being $399. Much the same as Sega's Master System, NEC's add-on was relatively difficult to find on store shelves. Insufficient localization effort for the add-on's pre-released Japanese library is another oft cited flaw of NEC's marketing strategy. So select, according to popular game magazines, was the Turbo CD localizations that the game media accuses NEC for single handedly killing the add-on.

The TurboGrafx and the Turbo CD-ROM were left with fewer titles, by a ratio of at least 7:1, in comparison to the Sega Genesis alone by the end of the 16-bit generation. In 1989 and 1990, however, the TG16 saw roughly the same amount of quality software releases as the Sega Genesis and Master System combined.25 By Spring of 1991 the TurboGrafx library had grown to the point that the main thrust of NEC's advertising campaign stated "It's easy to beat the competition when you've got them outnumbered."26 It was in fact only after the Super Nintendo and Sega CD were on the market in 1992 that the TG16's library dramatically lagged in software releases of notable quality.

According to inconsistent online sources, the TurboGrafx-16 only sold around 2.5 Million units in the US by 1993, a significant failure when compared to Sega's Genesis that sold over 20 Million in the US by 1995. The TG16's marketability effectively began and ended in 1990 when the Genesis proved to be the relative marketing success and Sega devoted all of its resources to toppling Nintendo's gaming empire. Yet the TG16-CD combination saw one more significant push in 1992, when Turbo Technologies Inc (TTI) launched the Turbo DUO. The tale of TTI's two systems in one will be discussed in greater detail in its own section.

- 1. Jonathan J. Burtenshaw, ClassicGaming.com's Museum NEC TurboGrafx-16 (TG16) - 1989-1993 (archive.org February 1, 2008)

- 2. TurboGrafx-16/Duo FAQ - By John Yu, Last revised: 05/25/95 (archive.org May 14, 2007)

- 3. emulationzone.org Turbo-Grafx/PC-Engine Emulation Sections (archive.org June 15, 2008)

- 4. GAMESX.com Forums, Console Mods, RobIvy64 (e-mail) "TG-16/PCE overclocking success!" (archive.org May 1, 2008)

- 5. 6 Waveforms, 1 Frequency Modulated Channel leaves 4 Waveforms, 1 Waveform Channel can become White Noise, all channels can be programmed for sound samples. Paul Clifford (e-mail), PC Engine Programmable Sound Generator (psg.txt) (accessed February 18, 2010) available from http://www.plasma.demon.co.uk/pcengine/; internet.

- 6. Clifford, psg.txt $0802 - Fine frequency adjust

- 7. Emanuel Schleussinger, PC-Engine Video Display Controller Documentation (vdcdox.txt), (February 1998, accessed March 19, 2010) available from http://www.zophar.net/documents/pce.html; internet.

- 8. Paul Clifford (e-mail), PC Engine Video Colour Encoder (vce.txt)(accessed February 18, 2010) available from http://www.plasma.demon.co.uk/pcengine/; internet.

- 9. Typically only 216 horizontal lines are visible and are either 256 or 320 pixels wide, Schleussinger, (vdcdox.txt) 5. The Sprites in the VRAM.

- 10. Sixteen 15 Color palettes for the background, sixteen 15 Color Palettes for Sprites, Clifford, (vce.txt).

- 11. Clifford, (vce.txt).

- 12. Nimai Malle (e-mail), pce_doc Video Sprites (accessed March 20, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org/?page=PC%20Engine

- 13. Actual limit may be 8 due to 16 pixel wide sprites being aligned as 32 pixel sprites, Malle, pce_doc Video Sprites

- 14. Scaling is the technical term for a two dimensional object that moves closer or further away from the screen in an animated sequence. The term does not included animated sprite transitions to simulate the same effect.

- 15. "16-bit Sizzler," Electronic Gaming Monthly, May 1989, 30.

- 16. Steve Massey, "The Cutting Edge: The TurboGrafx-16," Gamepro, July 1989, 11.

- 17. Steve Harris, "Turbo to Increase Library of Titles," Electronic Gaming Monthly, December 1989, 50.

- 18. David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (New York: Random House, 1993), 215.

- 19. Steven L. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001), 423.

- 20. "Slasher Quan," "So, You Want to Buy A 16-Bit System...", Gamepro's 16BIT Video Gaming, February 1992, 7.

- 21. Sheff, Game Over, 351.

- 22. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games, 449-450.

- 23. Tom R. Halfhill, "Software Shakeout," Game Players, January 1991, 4.

- 24. Notable Games: 1989-1990, http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

- 25. Notable Games: 1989-1990, http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

- 26. Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1991, 28-29.

Sega Genesis vs Super Nintendo

| Lifespan: | 1989-1996 |

|---|---|

| CPU: | 7.67 MHz 16/32-bit 680005 |

| Co-Processors: | 3.58 MHz Z80 (Audio/SMS): Can write to 68000's Work RAM6 Can access cartridge's ROM data7 Texas Instruments 76489 (PSG Audio): 4 Channels 8 Yamaha 2612 (FM Audio):9 6 Channels: One 8-bit Stereo Digital Audio Channel (DAC) replaces one FM channel 10 10 Audio Channels total Output Frequency: 52 kHz |

| Video Processing: | VDP Master System Compatibility 11 Hardware Shadow and Lighting 12 Direct Memory Access (DMA): Transfer Rate: 7.2 KB per 1/60th second13 |

| Resolutions: | 256x224, 320x224, 320x448 14 |

| Work RAM: | 64 KB |

| Video RAM: | 64 KB |

| Audio RAM: | 8KB |

| Color RAM: | 72 Bytes 15 |

| VSRAM: | 40 Bytes 16 |

| Colors On Screen: | 61 (30-75 in game, average 50) 17 18 |

| Color Palette: | 512 |

| Sprite Max & Sizes: | 80 sprites at 320x224 64 sprites at 256x22419 Sprite Sizes: 8x8, 8x16, 8x24, 8x32 16x8, 16x16, 16x24, 16x32 24x8, 24x16, 24x24, 24x32 32x8, 32x16, 32x24, 32x32 20 |

| Sprites per Scanline: | 20 at 320x224, 16 at 256x224 21 |

| Background Planes: | 2 layers with 16 colors per 8x8 pixel tile22 VDP handles scrolling as single planes, independently scrolling 8 line rows, and independently scrolling lines.23 Each 8 line row can can be displayed over or under others. 24 |

| Storage: | Cartridge up to 32 Mbit (4 MByte) Bankswitch method allows more than 32 Mbit of storage.25 |

| Lifespan: | 1991-1997 |

|---|---|

| CPU: | 3.58 MHz 16-bit 65c816 31 6502 Compatibility (unused) |

| Co-Processors: | SPC700 (Sound CPU) S-DSP (Sound Generator) 8 Digital Audio Channels Independent Stereo Panning (per channel)32 Filters for audio smoothing and echo 33 Compressed audio decoding 34 Output Frequency: 32 kHz |

| Video Processing: | PPU 1 PPU 2 (On the same chip) 35 Mozaic/Pixelation DMA Transfer Rate: 5.72 KB per 1/60th second shared by 8 Channels 36 HDMA Used for per line updates 37 |

| Resolution: | 256x224, 256x448, 512x224, 512x448 38 |

| Work RAM: | 128 KB |

| Video RAM: | 64 KB |

| Audio RAM: | 64 KB |

| Sprite RAM: | 512 + 32 bytes 39 |

| Color RAM: | 512 Bytes 40 |

| Colors On Screen: | 240-256 41 42 (90-150 average in game) |

| Color Palette: | 32,768 |

| Sprite Max & Size: | 128 sprites at: 8x8 & 16x16, 8x8 & 32x32, 8x8 & 64x64, 16x16 & 32x32, 16x16 & 64x64, 32x32 & 64x64, 16x32 & 32x64, 16x32 & 32x32 43 |

| Sprites per Scanline: | 32, 34 8x8 tiles, 256 sprite pixels per line 44 |

| Background Planes: | Eight Modes Numbered 0 - 7 4 (96-colors, 24 per background, 3/tile) 3 (two 120-colors, one 24-colors) 2 (120-colors) 2 (240-colors, 120-colors) 2 (240-colors, 24-colors) 2 (120-colors, 24-colors, interlaced) 1 (120-colors, interlaced) 1 (255-color, scaled, rotated, etc) 45 |

| Storage: | Cartridge up to 32 Mbit (4 MByte) • Tales of Phantasia (1995) (48 Mbit) • Star Ocean (1996) (48 Mbit) Average: 8 Mbit ('91), 16-32 Mbit ('92-'97) |

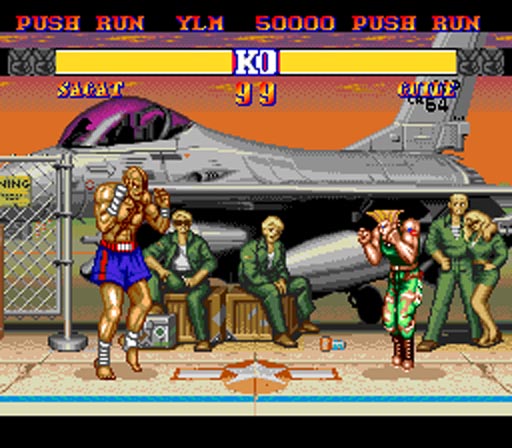

It is demonstrable that the SNES could actually display 2-3 times the colors on screen, while the Genesis could display 2-3 times the sprites and independently scrolling 2D planes. The SNES also could scale and rotate one 256 color plane, which could be made to look like large objects such as Bowser in Super Mario World or the Bomber in the first level of Contra IV. Alternately, games on the Genesis typically ran with less slowdown, featured faster scrolling levels, "tilted" sprites and backgrounds, and featured more custom special effects like scaling backgrounds and fully polygonal gameplay without any cart loaded processors. The Genesis' software effects are best seen in Contra Hard Corp, Castlevania Bloodlines, Batman and Robin, Ranger X, Sonic 3D Blast's bonus levels, LHX Attack Chopper, and Red Zone, for starters.

Much as was the case with the NES library, the Super Nintendo saw full fledged releases for several years after the Genesis was discontinued. Combined with the SNES's dominance in Japan, the system consequently had a larger worldwide library by the end of its cycle. Because Square and Enix released their titles exclusively, the SNES has a greater number of RPGs available for it in the US.

Much as was the case with the NES library, the Super Nintendo saw full fledged releases for several years after the Genesis was discontinued. Combined with the SNES's dominance in Japan, the system consequently had a larger worldwide library by the end of its cycle. Because Square and Enix released their titles exclusively, the SNES has a greater number of RPGs available for it in the US.

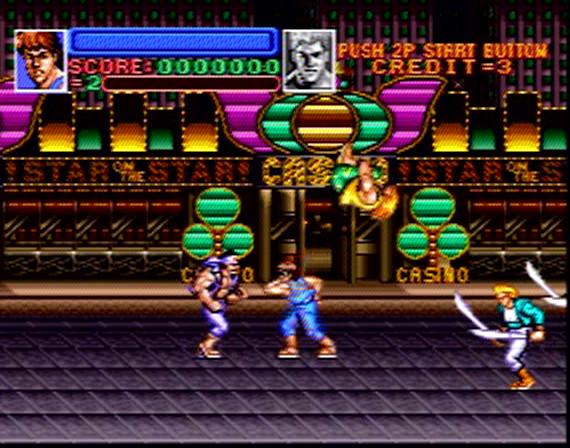

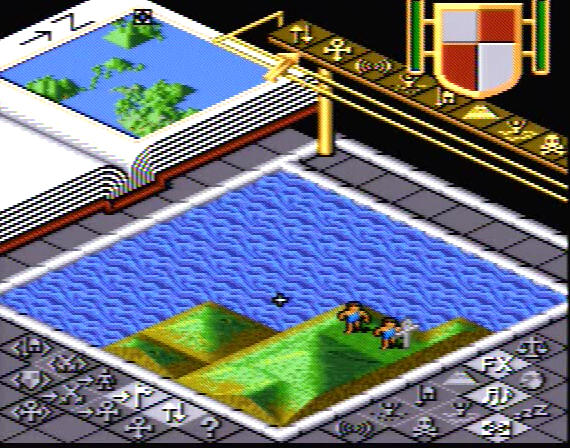

Despite superficial marketing tactics, the battle between NEC, Sega and Nintendo produced a wide variety of exclusive and critically acclaimed games for each platform. The Genesis has the largest library, and eventually gained the most third party support, of any Sega console. The Genesis' action genre is packed with arcade ports and unique home offerings like the Shinobi and Streets of Rage series. Yet the Genesis was also home to exclusive Sega RPGs like Sword of Vermillion, Phantasy Star 1-4, Shining in the Darkness, and Shining Force 1+2, amongst other notable series like Super Hydlide, Ys, and Dungeons & Dragons. Lunar the Silver Star, Lunar Eternal Blue and Vay, along with other Working Design’s localization efforts of Game Art’s games, were also released on the Sega CD.

Despite superficial marketing tactics, the battle between NEC, Sega and Nintendo produced a wide variety of exclusive and critically acclaimed games for each platform. The Genesis has the largest library, and eventually gained the most third party support, of any Sega console. The Genesis' action genre is packed with arcade ports and unique home offerings like the Shinobi and Streets of Rage series. Yet the Genesis was also home to exclusive Sega RPGs like Sword of Vermillion, Phantasy Star 1-4, Shining in the Darkness, and Shining Force 1+2, amongst other notable series like Super Hydlide, Ys, and Dungeons & Dragons. Lunar the Silver Star, Lunar Eternal Blue and Vay, along with other Working Design’s localization efforts of Game Art’s games, were also released on the Sega CD.

Regrettably, popular history uses the same measuring stick for all success stories. Sales is what most ill advised people look to in order to validate or invalidate their purchase decisions and sales is what the media is biased towards. The Genesis outsold the SNES in the US overall up until its discontinuation in 1995. The SNES managed to more than catch up in the two years before the Nintendo 64 took hold. The SNES clearly won out in sales worldwide and software sales in every region.

The truly important thing is that the war between the two companies produced some of the best games to ever be made. The game player that has only owned one system to the exclusion of the other has definitely lost out. What is worse is that in the new millenium the entire industry is bent toward anti-competative corporations. The preference for Mega-Corporations and Mega-Publishers are reflected by the media's excessively positive portrayal of the Super Nintendo.

- 1. Sam Pettus, "SegaBase Volume 3 - Megadrive / Genesis 'Sega MK-1601'," (January 23, 2007, accessed March 31, 2010) available from http://www.eidolons-inn.net/ (archive.org November 7, 2007).

- 2. Samuel N. Hart, A Brief History of Home Video Games: Sega Genesis, Geek Comix (archive.org June 16, 2008).

- 3. Legacy Sega Consoles: Sega Genesis, Sega of America (archive.org December 8, 2002).

- 4. PC Vs Console - Console Specs (4th Generation), (archive.org March 15, 2008).

- 5. Up to 32-bit processes internally, 16-bit data bus, Programer's Reference Manual M68000PM/AD Rev.1.

- 6. Are we sure MD Z80 can't write to M68K RAM? NCS does it....

- 7. Sega Genesis Manual.

- 8. 3 tone generators and 1 white noise, "Nemesis," GENESIS Technical Overview 1.00, (accessed April 1, 2010), 119.

- 9. Frequency Modulation is synthesized audio like PSG but considerably more complex.

- 10. Must be timed correctly in software to allow 5 FM Channels to play with digital audio (Street Fighter II:CE plays multiple digital audio channels simultaneously), "Nemesis," GENESIS Technical Overview 1.00, 92.

- 11. Charles MacDonald, E-mail || Homepage, Sega Genesis VDP documentation Version 1.5f (genvdp.txt) $01 - Mode Set Register No. 2, (August 10, 2000, accessed March 11, 2010), available from http://emudocs.org/?page=Genesis; internet.

- 12. MacDonald, genvdp.txt, 16.) Shadow / Hilight mode.

- 13. Speed at which data in RAM can be transferred to VRAM,"Nemesis," GENESIS Technical Overview 1.00, 45.

- 14. Interlaced double resolution mode, used in Sonic 2 splitscreen 2-player.

- 15. 64x9 bits, MacDonald, genvdp.txt, 9.) CRAM.

- 16. Vertical scroll RAM, 40x10 bits, MacDonald, genvdp.txt, 10.) VSRAM.

- 17. four 15-color palettes plus one background color

- 18. Direct 9-bit RGB (512 colors) available at half horizontal resolution, 160x224 or 128x224 visible, "Oerg866," "Nemesis" and "Chilly Willy," "Direct Color Demo using DMA," SpritesMind.net, accessed March 1, 2013, http://gendev.spritesmind.net/forum/viewtopic.php?t=1203.

- 19. MacDonald, genvdp.txt, 15.) Sprites

- 20. "Nemesis," GENESIS Technical Overview 1.00, 13.

- 21. MacDonald, genvdp.txt, Sprite Drawing Limitations.

- 22. Each tile shares colors from four 15 color palettes between the background and sprite layers, MacDonald, genvdp.txt, $0B - Mode Set Register No. 3.

- 23. MacDonald, genvdp.txt, $0B - Mode Set Register No. 3.

- 24. Hardware function of the VDP, MacDonald, genvdp.txt, 14.) Priority.

- 25.

"THE BANKSWITCHING MECHANISM",

SSFII GENESIS TECHNICAL INFORMATION. - 26. Samuel N. Hart, A Brief History of Home Video Games: Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Geek Comix (archive.org February 7, 2008).

- 27. Nintendo - Super NES - Detailed Specs, Nintendo of America (archive.org June 27, 2001).

- 28. PC Vs Console - Console Specs (4th Generation), (archive.org March 15, 2008).

- 29. Usenet, Rec.Games.Video, Ralph Barbagallo, SNES Hardware (January 19, 1992, accessed April 2, 2010) available from http://groups.google.com; internet.

- 30. Super NES Programming/SNES Specs, (October 29, 2007, archive.org June 14, 2008) available from http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Super_NES_Programming/SNES_Specs.

- 31. 1.56 MHz or 2.68 MHz in some software, Hardware.txt, available from http://www.mit.edu/afs/athena/activity/p/peckers/Programs/snes9x/solaris..., 65c816

- 32. SPC-700 Programming Information.

- 33. Anomie's S-DSP Doc version WIP (e-mail) (apudsp.txt), (October 13, 2005, accessed April 8, 2010).

- 34. "Ledi" and "Peekin", Super Famicomm Sound Manual NOA-SFX-04/15/90 (sfsound.txt), (October 15, 2001, accessed April 9, 2010), available from http://www.emudocs.org/?page=Super%20NES.

- 35. PPU is is called a single processor in all other documentation, Kevin Neviksti, SNES memory map and MAD-1 chip information (SNES_MemMap.txt), (accessed April 23, 2010) available from http://gatchan.net/uploads/Consoles/SNES/Flashcard/SNES_MemMap.txt.

- 36. 2.68MB divided by 8 (channels) divided by / 60 (frames per second), DMA occurs during VBLANK, Super NES Programming/SNES Specs, Direct memory access unit.

- 37. Uses DMA channels, Hardware.txt, H-DMA

- 38. 448 and 478 line modes are interlaced, Qwertie, Combined Registers Document (combined.txt), Screen mode/video select register [SETINI] (accessed on April 8, 2010).

- 39. Super NES Programming/SNES Specs, Video RAM.

- 40. Each color uses 2 bytes, David Piepgrass, Qwertie's SNES Documentation Plus DMA Revision 6 (2.1), Color Palettes, (1998, accessed April 5, 2010) available from http://emudocs.org (archive.org July 12, 2007).

- 41. eight 15 color background palettes, eight 15 color sprite palettes in most common graphic modes,

Charles MacDonald, E-mail || Homepage, SNES hardware notes (snestech.txt), CGRAM, (September 17, 2003, accessed March 11, 2010), available from http://www.emudocs.org/?page=Super%20NES - 42. 2048 Colors are technically possible using Direct Color Mode, Hardware.txt, Direct Colour Mode.

- 43. snestech.txt, Sprites

- 44. Super NES Programming/SNES Specs, Maximum onscreen objects (sprites).

- 45. 4 backgrounds limits colors per tile (8x8 pixels) to 3-colors whereas other modes are 15-colors per tile, adapted from Qwertie's SNES Documentation, Register $2105: Screen mode register (1b/W).

1989-1990: Competing with Speculation

Summer 1989, before NEC and Sega launched their 16-bit consoles, "Shooter" meant flying an advanced space craft against an evil armada and Nintendo, which owned ninety percent of the worldwide video game market, signified "video game."1 Before Fall, NEC focused its audience on the technical prowess of its newly dubbed TurboGrafx-16 and the merits of "16-bit gaming."2 NEC was not alone in advertising the generational leap, Sega also focused on a single characteristic turned marketing term for its new console, "16-bit."3 Undaunted, Nintendo Power, a magazine owned and operated by Nintendo, continued as it had for more than a year promoting Nintendo Entertainment System and then Gameboy portable games. Video game magazine start-ups Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) and Gamepro, however, mutually thrived on rumors and speculation about new hardware. In the same issues that extolled, for the first time, the soon-to-be released Genesis and TG16, both magazines devoted equal space to a "super" system from Nintendo.4 5 This represents an unprecedented public relations campaign for a game console that barely existed as a prototype.

Summer 1989, before NEC and Sega launched their 16-bit consoles, "Shooter" meant flying an advanced space craft against an evil armada and Nintendo, which owned ninety percent of the worldwide video game market, signified "video game."1 Before Fall, NEC focused its audience on the technical prowess of its newly dubbed TurboGrafx-16 and the merits of "16-bit gaming."2 NEC was not alone in advertising the generational leap, Sega also focused on a single characteristic turned marketing term for its new console, "16-bit."3 Undaunted, Nintendo Power, a magazine owned and operated by Nintendo, continued as it had for more than a year promoting Nintendo Entertainment System and then Gameboy portable games. Video game magazine start-ups Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) and Gamepro, however, mutually thrived on rumors and speculation about new hardware. In the same issues that extolled, for the first time, the soon-to-be released Genesis and TG16, both magazines devoted equal space to a "super" system from Nintendo.4 5 This represents an unprecedented public relations campaign for a game console that barely existed as a prototype.

Marketing hype did not only affect video game related magazines. Journalist David Sheff, who authored Game Over in 1993, described most of the TurboGrafx game library as "not fun" or "unexceptional" to explain why the system's sales lagged behind competitors. Sheff also stated "the best entertainment-software companies were too busy making Nintendo games to bother making ones for TurboGrafx."6 Dismissing the early Genesis library as "sports games and arcade knockoffs," Sheff explained that Genesis developers created "great-looking games ... but not great-playing games."7 Sheff's analysis reflects the majoritarian view in the game industry from the late 1990s on, and is probably a result of his many developer and executive interviews rather than personal play time. Yet game reviews, and press coverage in general, were consistently more positive of the Genesis and TG16 than they were of Nintendo's NES from 1989 and 1990.

Marketing hype did not only affect video game related magazines. Journalist David Sheff, who authored Game Over in 1993, described most of the TurboGrafx game library as "not fun" or "unexceptional" to explain why the system's sales lagged behind competitors. Sheff also stated "the best entertainment-software companies were too busy making Nintendo games to bother making ones for TurboGrafx."6 Dismissing the early Genesis library as "sports games and arcade knockoffs," Sheff explained that Genesis developers created "great-looking games ... but not great-playing games."7 Sheff's analysis reflects the majoritarian view in the game industry from the late 1990s on, and is probably a result of his many developer and executive interviews rather than personal play time. Yet game reviews, and press coverage in general, were consistently more positive of the Genesis and TG16 than they were of Nintendo's NES from 1989 and 1990.

Emblazoned on the November 1989 cover of EGM was a close up screen image of Sega's award winning Ghouls n' Ghosts conversion for Genesis and a stamp reading "SEGA * SEGA: More Master System More Genesis." Steve Harris, Editor and Publisher of EGM, was pressured enough by readers to introduce his fourth issue excusing his magazine's tendency for Nintendo content.8 Harris also dedicated one fifth of his editorial to "owners of other machines" such as the TG16, and Atari systems. David White, an Associate Editor for EGM, maintained in the same issue that a "video game system is only as good as the games it plays" and asserted the TurboGrafx was the one system that stood above the crowd in this respect.9 In addition to reminding his audience of the ease of localizing successful PC-Engine titles to the TG16, White also began his Sega Genesis editorial with a full page about Sega Master System compatibility.10

Fall 1989 issues of Game Player's, a long running electronics magazine, dedicated dozens of pages to NES software and news, but had much to say about 16-bit consoles and their games. In a multi-page spread, Editor-In-Chief Tom Halfhill argued the merits of Sega's Altered Beast, which was a pack in game for the Genesis. Among his qualifications for "true arcade quality in your living room" Halfhill listed detailed and colorful screens that include multiple scroll layers, which he asserted "create an illusion of three dimensions." Smoothness and speed of character animation, "voice synthesis and stereo sound," and two player cooperative play were also listed as next-generation advantages due to "advanced computer chips inside the Genesis."11 Halfhill used similar terms when discussing the TurboGrafx CD-ROM add-on.12 Like EGM's David White though, Halfhill reasoned the merits of 16-bit gaming primarily in the context of game quality and reminded his audience that licensed games boosted console sales more than graphic and sound quality.13

Even in the new millennium, gameplay related comments on the Internet shine a dim light on at least three dozen worthwhile games released for the Genesis and nearly sixty for the TG16 by the end of their first full year.14 Among these games' developers were Data East, Hudson, Irem, Namco, NCS, and Victor for NEC's console and Asmik, Sunsoft, Electronic Arts, and Renovation for Genesis. Even without NEC and Sega's own offerings, these early third parties contributed greatly to the launch and first year libraries of both 16-bit consoles. Nintendo's NES had a monopoly on software developers and sales during these formative years, but exclusive and well received software was shared by all three of these game consoles.

Gamepro accordingly progressed from its premier issue moniker "The Nintendo, Sega, and Atari Video Game Magazine," to include TurboGrafx, Genesis and Gameboy by the beginning of 1990. All game magazines were still subject to the dominant force in the industry. The majority of all game magazine advertisements in Gamepro and EGM during 1990 were for NES software, but majority rule affected EGM far more than Gamepro. EGM's Steve Harris contended, in summer of 1990, for his magazine's multi-platform objectivity even while he defended its position that the Genesis had proven itself "better" than the TurboGrafx-16.15 In the same issue that Harris argued EGM's judgments were exclusively about published games, EGM declared the still unnamed Super Nintendo "superior to anything that has every (sic) before been created." 16

Gamepro accordingly progressed from its premier issue moniker "The Nintendo, Sega, and Atari Video Game Magazine," to include TurboGrafx, Genesis and Gameboy by the beginning of 1990. All game magazines were still subject to the dominant force in the industry. The majority of all game magazine advertisements in Gamepro and EGM during 1990 were for NES software, but majority rule affected EGM far more than Gamepro. EGM's Steve Harris contended, in summer of 1990, for his magazine's multi-platform objectivity even while he defended its position that the Genesis had proven itself "better" than the TurboGrafx-16.15 In the same issue that Harris argued EGM's judgments were exclusively about published games, EGM declared the still unnamed Super Nintendo "superior to anything that has every (sic) before been created." 16

Nintendo's brand and largely incorrect hardware specifications was the only proof EGM needed of the SNES's preeminence. Harris' magazine listed the rarely used 512x448 interlaced resolution and 256 color modes for the SNES as though they would be used in the average game. A six page spread printed in EGM's December issue dubbed the Super Nintendo as "the ultimate in 16-Bit gaming" even before its Japanese launch.17 Gamepro, which had a special section every issue titled "The Cutting Edge," notably lacked any pre-launch editorials of the "ultimate" 16-bit console after its second issue back in 1989.

Notable hardware, like NEC's portable TurboGrafx-16 the Turbo Express, were given full attention by Gamepro but suffered attached editorials about the Super Nintendo in EGM.18 19 As a result of these two magazines' competing views all three console manufacturers received much needed free publicity. EGM reasonably presumed that the next Nintendo console would take over when it was eventually released. Gamepro, which apparently was not sending representatives to Japan at the time, represented a more impartial exposition of new games and hardware. Only the next year could tell what the American public actually wanted, but it was evident by the end of 1990 that Nintendo was losing its hold on the US game console industry.

Notable hardware, like NEC's portable TurboGrafx-16 the Turbo Express, were given full attention by Gamepro but suffered attached editorials about the Super Nintendo in EGM.18 19 As a result of these two magazines' competing views all three console manufacturers received much needed free publicity. EGM reasonably presumed that the next Nintendo console would take over when it was eventually released. Gamepro, which apparently was not sending representatives to Japan at the time, represented a more impartial exposition of new games and hardware. Only the next year could tell what the American public actually wanted, but it was evident by the end of 1990 that Nintendo was losing its hold on the US game console industry.

- 1. David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (New York: Random House, 1993), 349.

- 2. Sheff, Game Over, 351.

- 3. Steven L. Kent, The Ultimate History of Video Games (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001), 401.

- 4. Steve Harris, "The Amazing Super Nintendo," Electronic Gaming Monthly, August 1989, 39.

- 5. Steve Massey, "The Cutting Edge: Super Famicom. The Next Generation from Nintendo," Gamepro, July 1989, 13.

- 6. Sheff, Game Over, 351-52

- 7. Sheff, Game Over, 355

- 8. Steve Harris, "insert coin: You Asked For It, You Got It... More Sega!!!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, November 1989, 6.

- 9. David White, "Turbo Champ: TurboGrafx Explodes With Games!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, November 1989, 64.

- 10. David White, "Outpost: Genesis, The Master System Lives On!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, November 1989, 70.

- 11. Tom R. Halfhill, "Altered Beast: Arcade Action On The Genesis," Game Player's, October 1989, 42-44.

- 12. Halfhill, "NEC's TurboGrafx-16 CD: Plenty Of Potential," Game Player's, October 1989, 18-22.

- 13. Halfhill, "The EDITORS VIEW," Game Player's, November 1989, 4.

- 14. Notable Games: 1989-1990, http://www.gamepilgrimage.com.

- 15. Steve Harris, "The Genesis/Turbo Debate Concludes...," Electronic Gaming Monthly, July 1990, 6.

- 16. "Super Famicom Update ... 16-Bit Nintendo Close To Production!!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, July 1990, 29.

- 17. "Super Famicom Special," Electronic Gaming Monthly Presents the 1991 Video Game Buyer's Guide, December 1990, 28.

- 18. "The Whizz," "The Cutting Edge: The TurboExpress Handleld System," Gamepro, August 1990, 18.

- 19. NEC To Show Turbo Express at CES...First On-Hands Tests Reveal Superiority," Electronic Gaming Monthly, July 1990, 30.

1991: Hype vs Reality

Not until March 1991 did issues of Gamepro and Game Players dedicate an editorial to the Super Nintendo. Unlike EGM's numerous articles comparing specifications provided by marketing departments, both Gamepro and Game Player's focused on the games that had already been released in Japan. Gamepro exhibited pictures of Super Mario World, F-Zero and Final Fight, while pointing squarely at the "massive support by third-party licensees" as the system's biggest advantage.1 Game Player's Tom Halfhill argued similarly that launch games for the Super Famicom, which was the console's final name in Japan, could have been made as well on the Genesis and TG16. Crassly dismissing exaggerated maximum color count and resolution differences for each system, Halfhill concluded "quality software and clever marketing are more likely to carry the day." 2 Marketing influenced more than the sales of these consoles or their games, it created the popular perception about the machines' capabilities and the quality of their libraries.

Not until March 1991 did issues of Gamepro and Game Players dedicate an editorial to the Super Nintendo. Unlike EGM's numerous articles comparing specifications provided by marketing departments, both Gamepro and Game Player's focused on the games that had already been released in Japan. Gamepro exhibited pictures of Super Mario World, F-Zero and Final Fight, while pointing squarely at the "massive support by third-party licensees" as the system's biggest advantage.1 Game Player's Tom Halfhill argued similarly that launch games for the Super Famicom, which was the console's final name in Japan, could have been made as well on the Genesis and TG16. Crassly dismissing exaggerated maximum color count and resolution differences for each system, Halfhill concluded "quality software and clever marketing are more likely to carry the day." 2 Marketing influenced more than the sales of these consoles or their games, it created the popular perception about the machines' capabilities and the quality of their libraries.

All game magazines that mentioned the Super Nintendo prior to its US launch noted something about its games displaying more colors on screen, but they disagreed on how significant the gap was. This disparity in journalist reviews was probably most influenced by the outputs and target of each of these system's graphics. TurboGrafx, Genesis and SNES consoles were packaged with RF cables intended for the coaxial cable input of an NTSC television, which was the standard in the US and Japan. Answering one Phil Kennington in the February 1991 issue, EGM ranked all available output cables for game consoles from RF, to Composite, and finally RGB. The editor also explained that EGM had to modify the hardware of all of their game consoles to support RGB monitors.

All game magazines that mentioned the Super Nintendo prior to its US launch noted something about its games displaying more colors on screen, but they disagreed on how significant the gap was. This disparity in journalist reviews was probably most influenced by the outputs and target of each of these system's graphics. TurboGrafx, Genesis and SNES consoles were packaged with RF cables intended for the coaxial cable input of an NTSC television, which was the standard in the US and Japan. Answering one Phil Kennington in the February 1991 issue, EGM ranked all available output cables for game consoles from RF, to Composite, and finally RGB. The editor also explained that EGM had to modify the hardware of all of their game consoles to support RGB monitors.

A consumer who wanted to view their console of choice with anything better than RF cables in 1991 had to buy a brand new television if they wanted to connect with AV Composite cables (Yellow video, with Red and White audio cables). Composite cables required an investment of twenty dollars in addition to a new television that would also improve cable and VCR quality. Obtaining a cable compatible with an RGB monitor required an investment of around one hundred dollars and a specialized monitor that cost significantly more than the new televisions being sold in electronics stores.3 EGM admitted that game companies targeted the lower quality outputs that the mass market could buy in stores, which severely impacted how many distinct colors could appear on the consumer's screens.4 Answering similar questions, Gamepro warned one Spanky Smith of Greensville South Carolina that Japanese RGB cables could have been incompatible with US equipment.5

Unencumbered by pertinent facts, EGM proceeded to advocate the "Super Famicom." Showing computer generated shots of three dimensional trees in a preview for Hole In One Golf, immediately following a four page promotion for Super Mario World, EGM explained "The Super Fami, with its large color palate(sic), can show shadings that give the illusion of 3-D." When Hal's Hole In One Golf was actually published that Fall it was notably absent of any three dimensional objects as shown in EGM's preview.6 Hole In One Golf actually does exhibit a unique feature of the Super Nintendo in the same manner of other launch titles. The SNES's Mode 7 allowed Hole in One Golf a fly by of a very low color two dimensional still image of the courses. Hole in One's courses were strictly overhead and two dimensional, with a special angled view that rendered the landscape in low detail to show elevation.7

During any generation of hardware, effects that the systems handled with the least programming effort are employed in games more often and more uniformly than effects that developers had to hand code. Mode 7 was marketed by Nintendo, and their allies, to become synonymous with real time scaling and rotation. Scaling is the term used for simulated zooming of backgrounds or characters, rotation allows the same to turn like a wheel. Mode 7 could only scale and rotate a single two dimensional background layer, no SNES game scales characters or objects in a Mode 7 scene. The effect was most often used to "jazz up" certain non-gaming scenes and racing games. Mode 7 offered nothing that was not technically already being done in similar scenes on other consoles, and was totally trumped by arcade machines from the late 1980s. The effect had a distinctive look, however, and its frequent use was the most obvious characteristic of Super Nintendo games. These facts gave Nintendo the ability to easily point out the look and sound of Super Nintendo games and made rumors about the system's technical superiority seem true.

Introducing his April issue of EGM, Ed Semrad explained the importance of rumors to his readers and explained game magazines' function as free advertising for game companies. Semrad was also one of the first editors to print the term "vaporware" in regard to the Nintendo-Sony CD-ROM add-on for the affectionately abbreviated "Super Fami." 8 Even while Semrad lamented that "a very short nondescript press statement" tore the industry's attention from real consoles and games, the editor failed to note how similar that was to EGM's constant coverage of the SNES for the previous two years. In the previous issue's letter section, one T. Jones wrote that four different Nintendo representatives denied the accuracy of EGM's Super Famicom coverage so vehemently that their words were not fit for print. EGM responded that everything it had written about the SNES was correct regardless of the facts that the system name, its specifications and even the appearance of its games were significantly different in the final product.9

Introducing his April issue of EGM, Ed Semrad explained the importance of rumors to his readers and explained game magazines' function as free advertising for game companies. Semrad was also one of the first editors to print the term "vaporware" in regard to the Nintendo-Sony CD-ROM add-on for the affectionately abbreviated "Super Fami." 8 Even while Semrad lamented that "a very short nondescript press statement" tore the industry's attention from real consoles and games, the editor failed to note how similar that was to EGM's constant coverage of the SNES for the previous two years. In the previous issue's letter section, one T. Jones wrote that four different Nintendo representatives denied the accuracy of EGM's Super Famicom coverage so vehemently that their words were not fit for print. EGM responded that everything it had written about the SNES was correct regardless of the facts that the system name, its specifications and even the appearance of its games were significantly different in the final product.9

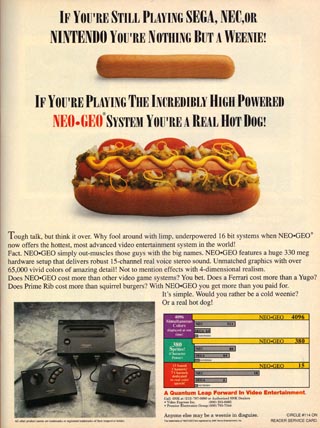

Hardware specifications in the game industry are only the product of marketing. It is evident from the published comments in all game related media that even the companies themselves were unsure of the technical limitations of their hardware. Advertising for the "consolized" NEO GEO arcade machine demonstrated the disparity between engineers and marketers very well. While SNK tried to convey that its arcade-machine-turned-console had "more" of everything, the TurboGrafx and Genesis specifications are reversed in two out of three categories.

Nintendo's public relations people out of Japan used similar terms to successfully, if inadvertently, convince EGM's publisher and editor to advertise the Super NES for several years in advance of its launch. As much as one million of the game industry's core demographic were exposed to EGM's Super Nintendo promotions every month. 10 By tossing out theoretical specifications without regard for television output, and knowing its audience did not have adequate programming knowledge of any system, Nintendo succeeded in establishing its upcoming console as "better" than anything else.

As a result of the Super Nintendo's preconceived superiority, the gaming media, retailers and public took an entirely different approach to Nintendo's second console than they did for the 16-bit consoles released two years prior. Instead of the usual skeptical "wait and see" consumer approach, the SNES might as well have already been a smashing success in all respects. The Genesis and TurboGrafx saw a couple of months of coverage prior to their US launch, which merely showed off the difference between their graphics and those of 8-bit consoles. The Super Nintendo, thanks largely to EGM, had seen monthly exposure for two years prior to its launch and enjoyed a full fledged buyer's guide in the August issues of Gamepro and EGM. Similar guides, that contained reviews, previews and pictures for every game announced for the US were finally published for the two existing 16-bit consoles the same year, which was two years after their US launch. Unfortunately for Nintendo, the hype failed to carry the NES' dominance into the new generation.

- 1. "The Unknown Gamer," "The Cutting Edge: Super Famicom Software," Gamepro, March 1991, 14.

- 2. Halfhill, "The Editor's View," Game Player's, March 1991, 4.

- 3. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, RGB For Genesis!..," Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1991, 10.

- 4. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, SFX, too good for TV??..," Electronic Gaming Monthly, February 1991, 10.

- 5. "The Mail, Making the Connection," Gamepro, December 1991, 14.

- 6. "The Super Famicom Times: Hole In One Golf," Electronic Gaming Monthly, February 1991, 86.

- 7. "Fanatic Fan," "Overseas ProSpects," Gamepro, July 1991, 14.

- 8. Semrad, "insert coin: The Power of Rumors...," Electronic Gaming Monthly, April 1991, 8.

- 9. "Interface: Letters To The Editor, No SFX in US.," Electronic Gaming Monthly, March 1991, 10-11.

- 10. Semrad, "insert coin, 1,000,000 Readers!," Electronic Gaming Monthly, June 1991, 8.

1991: Part 2, Value Propositions

Gamepro referred to the SNES library as "fully three-quarters ... upgrades from 8-bit programs," even while it referred to Super Ghouls N Ghosts as a "new generation." 1 Previews of the SNES library over the next five pages were oddly broken up by advertisements, the first two of which featured Genesis games prominently along with their prices. Over thirty five SNES games were previewed in typical promotional fashion however and almost all of them are made by third parties that owners of Nintendo's first console recognized.

Gamepro referred to the SNES library as "fully three-quarters ... upgrades from 8-bit programs," even while it referred to Super Ghouls N Ghosts as a "new generation." 1 Previews of the SNES library over the next five pages were oddly broken up by advertisements, the first two of which featured Genesis games prominently along with their prices. Over thirty five SNES games were previewed in typical promotional fashion however and almost all of them are made by third parties that owners of Nintendo's first console recognized.

Never to be upstaged, EGM dedicated twelve pages to the SNES Buyer's Guide within their August 1991 issue, which posted review scores for sixteen games and previews for thirty four more. EGM's review system had four separate reviewers rank a game on a scale of one to ten. The SNES buyer's guide ranked three games with nines and eights, five games scored eights and sevens, and eight more were scored four through six. That is, half of the SNES games reviewable at launch came recommended by EGM's reviewers, and half were relegated to mediocre or worse.2

In addition to amassing a large game library for the Genesis, Sega had debuted two things that summer which stole these magazine's spotlights from Nintendo. Sonic the Hedgehog and the Mega CD-ROM add-on combined with one hundred and fifty nine other Genesis games were impossible for game magazines, and by reflection consumers, to ignore.3 Sega's CD add-on for the Genesis will be dealt with in more detail in its own section, but its show floor debut in summer of 1991, months from its Japanese release, lent Sega significant media coverage. Sega also managed to spend more on advertising than ever before, as EGM's October issue contained a 96 page promotion for everything that was licensed for release on the Genesis.4

In addition to amassing a large game library for the Genesis, Sega had debuted two things that summer which stole these magazine's spotlights from Nintendo. Sonic the Hedgehog and the Mega CD-ROM add-on combined with one hundred and fifty nine other Genesis games were impossible for game magazines, and by reflection consumers, to ignore.3 Sega's CD add-on for the Genesis will be dealt with in more detail in its own section, but its show floor debut in summer of 1991, months from its Japanese release, lent Sega significant media coverage. Sega also managed to spend more on advertising than ever before, as EGM's October issue contained a 96 page promotion for everything that was licensed for release on the Genesis.4

During the Christmas season of 1991 EGM and Gamepro printed reader letters and 16-bit buyer's guides  that defined the game industry as a three way race with Sega and Nintendo roughly equal in all respects. Reader letters showed a disparity rarely seen in the US game industry over which system carried absolute superiority. One William Miller of Lawndale California simplistically compared popular Genesis and SNES games, the two system's central processors, and included the Sega CD to conclude "the S-NES is totally lame." Meanwhile Brian McSwain of Sanford Florida felt that the Sega CD would merely bring the Genesis to equality with the SNES' "graphics, sound, play control and Mode 7." John Sikes of Detroit Lakes Minnesota assumed that most of the advantages that the Sega CD would provide were already offered by the TurboGrafx-16 CD-ROM attachment. EGM itself responded to Ron Ward of Newark California to point out that the Sega CD would have more RAM than the Turbo CD and would be more proficient at scaling and rotation than the SNES' Mode 7. Noah Freer of Los Angeles just wrote in to compliment Sega's 96 page advertisement in EGM's October issue.5

that defined the game industry as a three way race with Sega and Nintendo roughly equal in all respects. Reader letters showed a disparity rarely seen in the US game industry over which system carried absolute superiority. One William Miller of Lawndale California simplistically compared popular Genesis and SNES games, the two system's central processors, and included the Sega CD to conclude "the S-NES is totally lame." Meanwhile Brian McSwain of Sanford Florida felt that the Sega CD would merely bring the Genesis to equality with the SNES' "graphics, sound, play control and Mode 7." John Sikes of Detroit Lakes Minnesota assumed that most of the advantages that the Sega CD would provide were already offered by the TurboGrafx-16 CD-ROM attachment. EGM itself responded to Ron Ward of Newark California to point out that the Sega CD would have more RAM than the Turbo CD and would be more proficient at scaling and rotation than the SNES' Mode 7. Noah Freer of Los Angeles just wrote in to compliment Sega's 96 page advertisement in EGM's October issue.5

Despite the incongruity of comments EGM held nothing back in favor of the Super Nintendo. In EGM promotion speak the SNES was "unlike any other consumer game system," and it captured "the crisp color and detailed graphics that today's players are demanding." The magazine also listed the system's advantages as scaling, rotation and audio and its disadvantages as slowdown, flicker, and limited objects on screen.6 That objects on screen observation is particularly important, as the Super NES is supposed to have the strongest "sprite engine" of the three 16-bit consoles by a wide margin. Whether the cause be its slower CPU or poor programming, SNES games always struggle to put as many characters and objects on screen as top TG16 games. Genesis games handily beat both the TG16 and SNES libraries in the category of sprites on screen. In order for the SNES to live up to its prelaunch hype as a "16-bit Mega Monster" and the "Ultimate in 16-bit gaming" these deficiencies needed to be ironed out.

Despite the incongruity of comments EGM held nothing back in favor of the Super Nintendo. In EGM promotion speak the SNES was "unlike any other consumer game system," and it captured "the crisp color and detailed graphics that today's players are demanding." The magazine also listed the system's advantages as scaling, rotation and audio and its disadvantages as slowdown, flicker, and limited objects on screen.6 That objects on screen observation is particularly important, as the Super NES is supposed to have the strongest "sprite engine" of the three 16-bit consoles by a wide margin. Whether the cause be its slower CPU or poor programming, SNES games always struggle to put as many characters and objects on screen as top TG16 games. Genesis games handily beat both the TG16 and SNES libraries in the category of sprites on screen. In order for the SNES to live up to its prelaunch hype as a "16-bit Mega Monster" and the "Ultimate in 16-bit gaming" these deficiencies needed to be ironed out.

Instead of listing hardware specifications and eyeballing graphical glitches Gamepro listed the prices, described the game libraries and controllers, and forecasted what each system's library would be like in 1992. The Genesis was listed at $149 with Sonic The Hedgehog and one control pad, another controller brought the total cost to "only $30 less than a Super Nes." Sega's game library was described as "a terrific mix of licensed character games...sports simulations...arcade action carts...and Weird Funko-Dudes Lost in Outer Space." Game costs were $45-$60 although "8-megabit role playing games" were $75. Special note was given to the Power Base Converter, listed at $35, which allowed "backward compatibility with dozens of great 8-bit Master System titles." Wrapping up, Gamepro assured its readers that the next year would provide even more of the same qualities to the Genesis library, and numbered the total release list at one hundred and fifty nine.7

Instead of listing hardware specifications and eyeballing graphical glitches Gamepro listed the prices, described the game libraries and controllers, and forecasted what each system's library would be like in 1992. The Genesis was listed at $149 with Sonic The Hedgehog and one control pad, another controller brought the total cost to "only $30 less than a Super Nes." Sega's game library was described as "a terrific mix of licensed character games...sports simulations...arcade action carts...and Weird Funko-Dudes Lost in Outer Space." Game costs were $45-$60 although "8-megabit role playing games" were $75. Special note was given to the Power Base Converter, listed at $35, which allowed "backward compatibility with dozens of great 8-bit Master System titles." Wrapping up, Gamepro assured its readers that the next year would provide even more of the same qualities to the Genesis library, and numbered the total release list at one hundred and fifty nine.7

NEC's console was by contrast introduced with a zinger about its 8-bit CPU making it "less advanced" than the Genesis or SNES. The Turbo CD attachment was brought up only to mention that it was not selling well and that Sega and Nintendo would likely release something similar. The TurboGrafx retail package cost $99 with one controller and Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. To which Gamepro complained about why Keith Courage, released in 1989, had not been replaced with the $50 "Mario equivalent" Bonk's Adventure. Also of note is that the TurboGrafx required an expensive peripheral called the Turbo Booster or Turbo Booster Plus, $35 or $60 respectively, to hook up with newer televisions using Composite A/V cables. In addition, to play multiplayer games on the TG16 one had to purchase an extra controller at $20 and a TurboTap 5-Player Adapter at $20.8 Assuming that Gamepro was correct to compare the value proposition of each system, the Turbo Booster, TurboTap and an extra controller alone brought the total starting cost to the same as a Genesis with an extra gamepad. Adding any game from 1991 to the mix sent the total cost of the "entry level" TG16 over $200.9 Gamepro proceeded to trash the TG16's library as limited and quirky to US audiences, before explaining that it had "bottomed out" for players without the CD add-on. The Turbo CD itself was priced at $299 and its games cost between $19 and $62. The total library for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Turbo CD at the end of 1991 was reported to be sixty-seven "regular games" and fourteen CD games.10

NEC's console was by contrast introduced with a zinger about its 8-bit CPU making it "less advanced" than the Genesis or SNES. The Turbo CD attachment was brought up only to mention that it was not selling well and that Sega and Nintendo would likely release something similar. The TurboGrafx retail package cost $99 with one controller and Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. To which Gamepro complained about why Keith Courage, released in 1989, had not been replaced with the $50 "Mario equivalent" Bonk's Adventure. Also of note is that the TurboGrafx required an expensive peripheral called the Turbo Booster or Turbo Booster Plus, $35 or $60 respectively, to hook up with newer televisions using Composite A/V cables. In addition, to play multiplayer games on the TG16 one had to purchase an extra controller at $20 and a TurboTap 5-Player Adapter at $20.8 Assuming that Gamepro was correct to compare the value proposition of each system, the Turbo Booster, TurboTap and an extra controller alone brought the total starting cost to the same as a Genesis with an extra gamepad. Adding any game from 1991 to the mix sent the total cost of the "entry level" TG16 over $200.9 Gamepro proceeded to trash the TG16's library as limited and quirky to US audiences, before explaining that it had "bottomed out" for players without the CD add-on. The Turbo CD itself was priced at $299 and its games cost between $19 and $62. The total library for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Turbo CD at the end of 1991 was reported to be sixty-seven "regular games" and fourteen CD games.10

The Super Nintendo segment placed it at the "top-of-the-line price of $199.95," which included Super Mario World and two controllers. The Genesis and TG16 controllers were described in the previous sections, with the Genesis pad having a total of three "fire buttons" a start button and a directional pad and the TG16 pad being "the same as the NES." The SNES pad was conversely called "the most advanced anywhere" and potentially "too complex" for children. Nintendo's 16-bit library was presented as updates to NES games, with the cons being disappointing sequels and no NES compatibility. Gamepro's final analysis boiled down to "price, games, hardware power, and future expansion." The TurboGrafx was relegated to the "low end" inexpensive entry system with "psuedo 16-bit" shooters and multiplayer games. The TG16 was clearly excluded from Gamepro's consideration, which consumers had apparently already done, so the value proposition left only Nintendo and Sega products. The Genesis and SNES were portrayed as roughly equal in hardware capabilities, with the SNES' Mode 7, higher colors and "stronger sprite engine" being offset by being "only half the speed of the Genesis." In terms of library the Genesis was unequivocally found to have won by a landslide in 1991.11

The Super Nintendo segment placed it at the "top-of-the-line price of $199.95," which included Super Mario World and two controllers. The Genesis and TG16 controllers were described in the previous sections, with the Genesis pad having a total of three "fire buttons" a start button and a directional pad and the TG16 pad being "the same as the NES." The SNES pad was conversely called "the most advanced anywhere" and potentially "too complex" for children. Nintendo's 16-bit library was presented as updates to NES games, with the cons being disappointing sequels and no NES compatibility. Gamepro's final analysis boiled down to "price, games, hardware power, and future expansion." The TurboGrafx was relegated to the "low end" inexpensive entry system with "psuedo 16-bit" shooters and multiplayer games. The TG16 was clearly excluded from Gamepro's consideration, which consumers had apparently already done, so the value proposition left only Nintendo and Sega products. The Genesis and SNES were portrayed as roughly equal in hardware capabilities, with the SNES' Mode 7, higher colors and "stronger sprite engine" being offset by being "only half the speed of the Genesis." In terms of library the Genesis was unequivocally found to have won by a landslide in 1991.11

Much more prone to hyperbole, EGM asserted that "1991 saw the first real explosion of 16-bit interest, spurred largely by Nintendo and the long-awaited release of their Super Nintendo Entertainment System." Editor Ed Semrad also mentioned that price drops by both NEC and Sega and slowing NES game sales were defining characteristics of the year.12 Reducing thousands of letters each month to a few pages, EGM spent two columns of its December letter section over when the newly released Street Fighter 2 arcade game would be brought home to the Super NES.13 Street Fighter 2 is thought to have been responsible for revitalizing the arcade industry in the US, so its exclusive release on the SNES would have been very significant. Yet the battle for 16-bit supremacy was no longer one sided. D.J. Thomas of Houston Texas wrote EGM to ask which system and games won awards that year. EGM responded that it had released an entirely separate issue for the purpose of its annual awards stating "as to who won the best game of the year, and the best system of the year ... they're either Nintendo or Sega products."14

Much more prone to hyperbole, EGM asserted that "1991 saw the first real explosion of 16-bit interest, spurred largely by Nintendo and the long-awaited release of their Super Nintendo Entertainment System." Editor Ed Semrad also mentioned that price drops by both NEC and Sega and slowing NES game sales were defining characteristics of the year.12 Reducing thousands of letters each month to a few pages, EGM spent two columns of its December letter section over when the newly released Street Fighter 2 arcade game would be brought home to the Super NES.13 Street Fighter 2 is thought to have been responsible for revitalizing the arcade industry in the US, so its exclusive release on the SNES would have been very significant. Yet the battle for 16-bit supremacy was no longer one sided. D.J. Thomas of Houston Texas wrote EGM to ask which system and games won awards that year. EGM responded that it had released an entirely separate issue for the purpose of its annual awards stating "as to who won the best game of the year, and the best system of the year ... they're either Nintendo or Sega products."14

The SNES' primary weakness came up again as Doug Erickson of Chehalis Washington mused to EGM about why Nintendo went with a "slow processor" instead of a "80386 or 68000 series processor." Ignoring the ignorance over which x86 series processor was equivalent to the Genesis' CPU, Erickson's question is substantial for several reasons. Erickson's letter shows that EGM's readers had been bombarded by technical specifications enough to actually start questioning the engineering of a proprietary device as though they were qualified to do so. His assertion also shows that consumers in 1991 were comparing games across platforms and manufacturers. Nobody would have felt that the SNES was slow if they only compared it to Nintendo's NES. That is in contrast to what will happen in future generations where entire markets migrate to a new console without shopping other manufacturers' products. EGM revealed that "a lot of letters" like Erickson's were questioning Nintendo's engineering "wisdom," eliminating the likelihood that this letter was not representative of a typical consumer. The Japanese market's preference for slower moving Role Playing Games and that game developers would learn to better exploit the SNES' hardware were offered by EGM as alternative views to Erickson's and others.15 It should not be ignored, though, that this kind of exchange of generally negative comments would not have happened if Nintendo and its game advertising was still the dominant force in the industry.